Lisa “Lia” Coryell is headed to the 2016 Paralympics in Rio for the first time at the age of 51. In a group of Veterans making history as “firsts,” Coryell is the first woman Paralympic archer to qualify in the W1 division and make the USA Archery team. She’s also an Army Veteran.

Of Coryell’s seven teammates, two others are Veterans. Andre Shelby served 18.5 years in the Navy, and the first African American man to compete in compound archery. The first woman to qualify and compete in compound archery is Air Force Veteran Samantha Tucker.

Army Veteran Lia Coryell and Air Force Veteran Samantha Tucker, both members of the USA Archery team.

Together, they are part of the largest group of Veterans in history to participate in the Paralympics.

In her family, Coryell was a first generation high school graduate and one of eight siblings. Coryell joined the Army during her senior year in high school. She knew that if she didn’t go on to bigger things, her life wouldn’t be anything different from what she saw around her.

“I saw my family struggle; struggle to make a living, to feed their children, and it hurt me to see them struggle. I wanted to figure out a way to help myself by helping other people.”

Coryell never felt comfortable calling herself a Veteran. After being medically discharged from the Army at the age of 19, with only six months in, Lia used her vocational rehab benefit to go to school and get a degree from the University of Wisconsin in recreation and physical education, with her minor in recreation therapy. She completed an internship at the Milwaukee VA Medical Center in the spinal cord injury unit. At the time, she hadn’t heard of the Paralympics or VA’s Adaptive Sports Program.

Coryell went back to college, this time at the University of Wisconsin in Whitewater to pursue a teaching degree in secondary education and library and information science and become a teacher. She was selected to serve as a member of the board for the University’s student-Veteran advisory council. She was also the student representative for Student Veterans of America and helped to open the Military and Veteran Resource Center on the Milwaukee campus.

Interacting with Veteran students shaped her ideas about what it means to be a Veteran, and she first became comfortable identifying herself as a Veteran when she realized that it’s not about how much time you spend in the military.

“It’s about the willingness to step up and say, ‘I’m here and I’ll train, and I’ll do it.’ You don’t have to go to war or be injured in combat to wear the title proudly,” she said.

“You don’t have to go to war or be injured in combat to wear the title proudly.”

Before Coryell lost her ability to walk in 2012, she said, “life was really good, because I had purpose, my life had meaning, I had the ability to contribute to a group of Veterans and make their lives better. I had a mission and something to do.”

But when Coryell became wheelchair-bound, it was a physical struggle to continue working at the university. She went through grief counseling, felt suicidal and didn’t want to get out of bed in the morning. She had two teenage kids at home. She described feeling afraid of living and at the same time, afraid of dying. Her doctors switched her to palliative care, because her disease — which is similar to multiple sclerosis — was progressive and terminal. She said her physical challenges “looked like a death sentence.”

Then, Coryell found adaptive sports. She attended the 2013 and 2014 Summer Sports Clinic, hosted by VA and held in San Diego, California. She made the decision to go because she wanted to set an example for others, specifically the Veteran students she mentored at the University.

“Where mama duck goes, baby ducks follow,” she said.

Coryell’s first week in San Diego was a turning point for her. She found her involvement in adaptive sports to be the first step out of a self-described “darkness.”

“The Summer Sports Clinic was life changing for me. For the first time, from the day I got off that bus, I was an athlete. They never called us clients, or participants or campers. We were athletes.”

Coryell had previously participated in a VA-sponsored downhill skiing event, and a triathlon clinic in a program called Dare to Try. In 2014, she went back to the Summer Sports Clinic, this time as a mentor. The day she returned, she had a serious discussion with her kids about her future, and how she wanted to pursue archery seriously and competitively.

For too long, she felt like a burden. She would ask family and friends to help her by taking her to the store. They’d offer to go to the store for her instead, because taking her to the store required too much effort. She said she was okay with that, because she didn’t want to be a burden to anyone she cared about.

The VA Summer Sports Clinic made Coryell realize that she was not a burden. The staff there wanted her to succeed. She was finished letting people do things for her. She felt empowered. She’d gone surfing in the waves of California. She hand cycled on a bike she didn’t know existed, kayaked and shot a bow using her teeth, with a mitt slid over one arm.

Coryell realized there’s a reason why Veterans also make good athletes. She said the elements of sport are similar to the culture of the military. She was reminded of a military mantra of “improvise, adapt and overcome.” She looked around at the Summer Sports Clinic, saw Veterans with struggles like hers and told herself she was not a loser, and she wasn’t dying.

Coryell took the next step. Her children supported her part-time move to Colorado to begin archery training at the U.S. Olympic Training Center. They knew that if their mom wanted to compete at a level like the Paralympics require, she had to go. They asked her to start living again, which meant Coryell’s children had to take on a lot of responsibility, particularly her daughter, who was a young adult at the time.

Coryell says her daughter is her best friend, and without her she couldn’t have gone to Colorado to train for the upcoming games.

She’s also enormously proud of her son, who’s getting ready to deploy with the 101st Airborne out of Fort Campbell as a combat medic. Coryell said her son was young when he accompanied her to campus events for the student resource center, and decided he wanted to join the Army and become a medic after listening to stories from injured Veterans. He wanted to earn his own GI Bill, like those students.

On her road to Rio, Coryell performed well at the AAE Arizona Cup Para World Ranking Event and SoCal Showdown, as well as in the World Archery Para Championships Team Trials. After only 18 months of training, she made the USA Archery team and was selected to compete in the World Archery Para Championships and Parapan American Championships teams. She traveled to Germany to represent the U.S. at the 2015 World Archery Para Championships, which was her first international competition, and her first time traveling internationally. Coryell will shoot a compound bow in the W1 women’s category at the upcoming 2016 Paralympics in Rio.

The VA National Veterans Sports Programs & Special Events Office provides a monthly assistance allowance for disabled Veterans for qualifying athletes training in Paralympic sports. VA’s Grants for Adaptive Sports Program provides grant funding to organizations to increase and expand the quantity and quality of adaptive sport activities disabled Veterans and members of the Armed Forces have to participate in physical activity within their home communities, as well as more advanced Paralympic and adaptive sport programs at the regional and national levels.

“Empowering the Veteran, teaching them they don’t have to carry the load, that they’re not alone. To me, that’s huge. That’s why I do it,” said Coryell. “I made the switch to live it like I mean it. I get up in the morning and remember that today was never a guarantee. I need to live every day like I mean it, to commit to it and to do something positive.”

In a 2015 interview, Coryell told World Archery, “Not in my entire life would I think I would be wearing the colors of the United States with my name on the back.” In Rio, she will be wearing them, with pride.

The Paralympics begin on Sept. 7. Out of 289 total athletes, 35 military Veterans and active duty Servicemembers are scheduled to compete.

Topics in this story

More Stories

VA remains open for business and is closely monitoring the Change Healthcare (CHC) cybersecurity incident.

Carry The Load, an organization dedicated to remembering the fallen, will visit 34 VA National Cemeteries traveling 20,000 miles along five separate routes covering all continental 48 states known as the National Relay for Memorial May 2024.

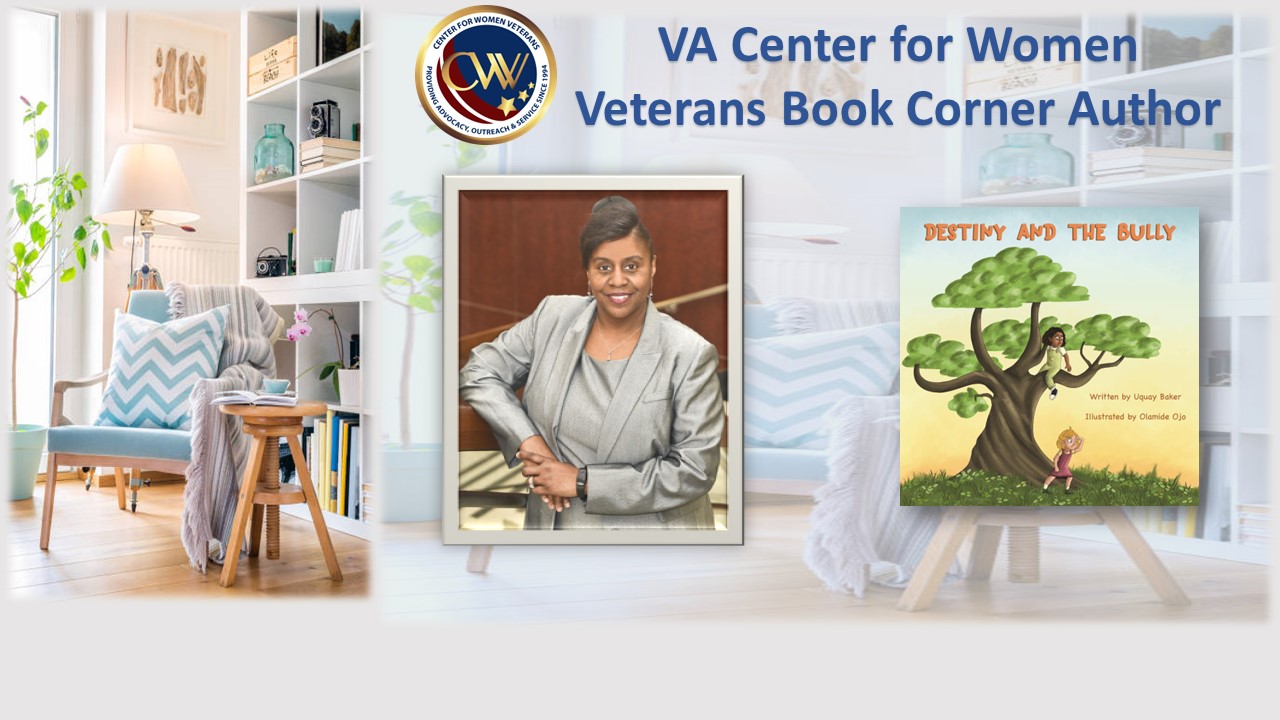

This month’s Center for Women Veteran Book Corner author is Army & Marine Corps Veteran Uquay E. Baker, who served in Military Police and communications roles from 1995-2006.

Hi Megan

Author in Las Vegas wants to send you information about his books. Can you send a email contact.